The Art of Breathing in the West

by

Elémire Zolla

Source: Studies in Comparative Religion, Vol. 2, No.3. (Summer 1968) © World Wisdom, Inc.

www.studiesincomparativereligion.com

DIADOCUS, an Epirote bishop of the Vth Century, made the doctrine of Euagrius and Macarius known in Byzantium : this was the most distant visible seed of the Art of Breathing in the West.

In the XIth Century Simeon the Younger, abbot of Xerokerkos, taught, in his On Sobriety and Attention, the way of breathing attuned with prayer and those who followed that way were called Hesychaxontes or Hesychasts, that is to say questers of quietude, of peace.

Among them was Nicephorus the Hesychast, an Italian converted from Catholicism, who became a monk on Athos after a stay in Byzantium under Michael the VIIIth Palaeologus (1261-1282) ; he wrote On Guardianship of the Heart, where with a confidential, almost popular air he answers the question : "How to obtain attention ?" His doctrine was summed up in the Method of Holy Attention, by an anonymous author.

Gregorios of Sinai was a monk on Sinai who afterwards went to Crete where his brother Arsenius taught him the Prayer of the Heart, (or attention of the heart) which he in his turn taught in a monastery on Athos. He distinguishes two ways of prayer, the subtle or hesychastic, and the customary one, psalmodic. Since psalmody was a symbol of Christian living in the West—representing the union of knowledge and active life, their meeting-point where one gains a non-operative cognizance of the divine[1]—the efficacy of the new way based on breathing must have been powerful indeed thus to become finally recognised in the face of the more usual method.

Meanwhile Gregorios Palamas (born in 1296) was being brought up in Byzantium at the court of the pious Andronicos II, the Emperor who had refrained from repeating a question he put to a counsellor deep in his prayers for fear of disturbing him. It was this Byzantium which in the young Gregorios bore the fruit of its short-lived and perfect theocracy. In 1316 he gave up the honours to become a monk ; himself a Hesychast master, he lived as a hermit, coming down to the monastery only for liturgic celebrations. In Byzantium, however, the Calabrian Barlaam of Seminaria was gaining authority ; he wanted to be initiated in the Hesychast tradition but soon, embittered and scornful, turned against it. In his list of what seemed to him to be Hesychast follies one may catch a glimpse of certain esoteric secrets whose trace one would look for in vain in the recorded texts ; thanks to the mockeries of an enemy something of the occult doctrines and practices leaks out. The list is contained in a letter (the Vth to Ignatius):

" ... the extraordinary separations and reunions of spirit and soul, the demons' commerce with the latter, the differences between white and red light, the intelligible entering and issuing through the nostril in tune with the breathing, the hands clasped over the navel, the union of Our Lord with the soul which is arrived at inside the navel in sensible guise and full of heartfelt certitude."

Palamas replied with the work Triads for the Defence of the Hesychast Saints, and in 1341 the councils of St. Sofia gave him their approval so that Barlaam withdrew to Italy there to become a Catholic bishop. The crux of the controversy between the two is summarized in the question whether the light shining on the Hesychast be the very essence of God like the light manifested to the disciples on Mount Tabor. Barlaam argued that it could not be so since two divinities would ensue, the visible and the invisible. Palamas replied claiming the saints' capacity to attain a sensible experience of the first-fruits of the Kingdom of Heaven, revealed in the shape of shining light : he would distinguish not two divinities but a God from whom three Persons would proceed, as from a single nature or essence, whence properties or energies would naturally originate, these being distinct yet not separable from the nature or essence, which is itself inseparable from the three distinct Persons. Invisible in itself and by itself, just as the face that makes itself visible in the mirror although remaining for itself in itself invisible, such is the divine substance ; we may discern its energy or its rays. In 1351 the synod held under John Catacunzenos maintained as orthodox dogma the uncreated light of Tabor.

From then on Byzantine mysticism thrived freely, both as a detailed meditation of liturgical symbols (Nicholas Cabasilas who died in 1391, author of The Life in Christ, touched the summit of this speculation) and also as Hesychast practice (whereof the most accomplished exposition is contained in the Centuria of the monks Ignatius and Callistus ; the only information about them is that Callistus was patriarch of Byzantium in 1397).

Two features of this mysticism have no equivalent in the Roman tradition : the mystic physiology and the theory of breathing.

The mystic points of the body, or the places in which one feels that one may "fix" the transfiguration taking place by degrees, are four : the first between the eye-brows, where thinking starts in a wholly abstract way and is subject to the temptation of arbitrary associations and digressions ; the second at the larynx, where thinking articulates into distinct though soundless words, remaining subject to temptations unless it knows how to coalesce into a prayerful ejaculation ; the third in the chest, the empty sound-box of articulate thought which, if it resounds, will rouse such an intensity of emotion as to stop all associations and digressions ; the fourth place is the one below the left breast where attention keeps watch against intruders as from a watch-tower. It may also be that the esoteric tradition included other such focal points : certainly the navel is one such, to which the first Hesychast text bears witness ; these points may well have been seven in number.[2]

This theory of breathing may appear difficult to a mind brought up on the writings of the Western saints. Nicodemus the Hagioretes found very few connections between the two stocks from this point of view. Together with the bishop Macarios of Corinth he published in Venice in 1782 a selection from the writings of monks from the Thebaid and of Byzantine saints under the title of Philokalia ; a translation of this work exists in English, by E. K. Kadloubovsky and G. E. H. Palmer, the publisher being Faber and Faber.

Breathing and the West

Where does one feel and think ? In the lungs was the Greek answer. The bronchia are stirred by the raging winds of love, in Sappho's verse, Aphrodite or Dionysus often breathe into them, a spell inflates them till they can stretch no further, the warriors advance breathing out fierceness. The heart is like a keel in the sea of blood on which the passions blow, according to Aeschylus' metaphor. A feeling is a rhythm imparted to the lungs : cowards do not expand their chest.

Breathing is used by the mystics as a term of comparison, and at times they even raise it to the status of sacramental action since inhaling resembles the breathing in of the Spirit, which will follow the breathing out or expulsion of one's own, personal spirit.

Jean-Baptiste Saint-Jure (1558-1657), one of the Jesuits who accepted the teaching of Bérulle, in his treatise L'union (1653), suggested the following prayer : "This is what our continuous occupation then ought to be, our favourite exercise : a perpetual breathing of Jesus Christ as our spiritual air, and then a breathing out and a returning of Him to God."

Breathing thus becomes a mirror of the Trinity : "As lungs and heart by their expansion attract air, so the soul attracts Our Lord when it opens and enlarges itself with its desires and its requests. Os meum aperui et attraxi spiritum : I have opened the mouth of my soul and attracted my spiritual aid, which is Our Lord who has said to the soul : Dilata os tuum et implebo illud, open your mouth quite wide and with great desires and I shall fill it up."

Although in Ignatius of Loyola's Exercises it is hinted that one should sanctify one's breathing by linking it constantly to its metaphoric function, only with the Hesychasts is it laid down that one should pray with the chin resting on the chest, holding one's breath.[3] Outside Christianity sacramental breathing is fundamental in yoga, which distinguishes the use of the two nostrils, the female nostril moon-like and cold being on the left, the male nostril sun-like and warm being on the right. The Indian yoga leads us to complexities ignored by the Western tradition, such as the entwining of two couples of opposites, breathing in and out on the one hand and, on the other, the passage of the breath to the right or the left.[4] Yoga moreover suggests the many positions in which the natural breathing can be evened out, until the soul like a feather hovers in mid-air motionless amid the opposing and balanced currents.[5] It is impossible to obtain a placid rhythm in breathing and at the same time be stirred by rage, envy, gluttony, lust or else be hampered by sloth, arrogance, avarice ; so that by acting upon breathing one will develop spiritual reflexes according to the maxim : act that you may feel (and that you may be).

Breathing therefore is not only a symbol of the soul's good conformation. It also has a sacramental capacity. It is but rarely that it is raised explicitly to sacramental level, but nevertheless language itself establishes a parallelism between holding one's breath and ecstasy. St. Theresa (Inner Castle, IV, III, 6) notices that mystical operations are soft and peaceful, while what is done with toil is more to detriment than to advantage (I call "done with toil" those actions requiring effort, like holding one's breath). The soul must abandon itself into the hands of God so that He may do with it whatever He wishes and it must accomplish all that is possible in order to resign itself to the divine will. This she writes in the fourth dwelling of the inner castle, i.e. the fourth moment of the mystical process leading to perfection, but when we reach the fifth dwelling she informs us that here all breathing ceases. It is very difficult to explain that an extreme softness of touch is the condition of every inward act and that a display of violence, however slight, means that one has lost control; perhaps this particular difficulty deterred St. Teresa from imparting notions on the methods of smoothing down the respiratory rhythm, since these fatally would have been mistaken for specific precepts.

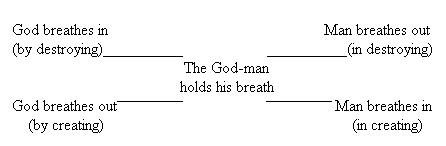

By breathing in, man receives God as Spirit and creates life in virile fashion ; by breathing out he expels the ego, in his feminine capacity of being moulded. Masters of arms teach their pupils to strike blows when the opponent is breathing out and to smite or to stiffen in defence and resistance while breathing in and also to bend down when breathing out.

God or the Kingdom of Heaven is the reverse of humanity. By breathing in, God slays (to exhale one's soul is to feel oneself being breathed in by the divine nostrils); by breathing out He sends the Spirit over the waters, He creates.

The point of junction between the two equal specular rhythms, the human and the divine, is the holding of one's breath : the androgyny that unifies the manly and the womanly aspect of breathing is symbolised by crucifixion, by the "wedlock of brother and sister." One holds one's breath when paying attention in a vertigo of awe and wonder, when one behaves like a dead man while still living ; all these conditions are mirrors to the two worlds, the celestial and the human.

Hindus and Hesychasts learn to hold their breath for a long time, which teaches one to breath in and out "as from the heels" ; in the same way he who yields and sacrifices, is destined to become rich and he who (behaves like one that) has, will receive in abundance. To breathe out well, to expel the ego, to free man from himself, laughing and crying are of great use ; he who cares about his rhythm, about his secret, the same will follow St. Paul's advice laughing with him who laughs and weeping with him who weeps, since either act leads a man to sighings of a healthy kind. For the same reason, singing can help one on the way towards liberation; American Indian death-songs can have such a mystical function.

Both laughing and crying stimulate breathing out, they expel demons and stale air; physical pain on the other hand brings breathing to an ecstatic halt ; it crucifies a man midway between breathing in and breathing out, a situation which makes it very difficult for one's idle imagination to visit the mind. One can make use of a pain by imagining it as similar to a boulder weighing down on the distinct pain purposely caused by not breathing in, after having completely emptied one's chest. One will learn to stay without breathing, in a state of painful intoxication that purifies one's mind from all idle imaginings.

In the long run both pains cease to be felt and become strangely absorbed by the body ; the body either is numbed as when quietened by morphine or else it lends itself, in a state of perfect inertia, to the pain's cutting : at this point the knife of pain seems graceful, sacrificial, like the knife of Lao Tsu's butcher who carves the joints without pressing at all, barely touching.

Pain is able to be used as fuel, providing the energy to transcend one's instinctual breathing. Once tasted, the mysterious powers bred of non-breathing (metaphorically described as levitation, ubiquity and so on) are insatiably stored up. What the world offers plentifully, quod ubique invenitur, pain upon pain, is not for the sake of the earthly and quite common enjoyment of pain, but in the same way as a Platonist like the Byzantine Nicetas Stathatos taught when he said that one should not be afraid to look upon beautiful creatures while wondering how base bodies can appear so alluring ; rather should one see them as fulcra whereby to avoid the snares attaching to earthly bodies even while recognising in them a trace of the Real Beauty.

Pain is like a raw material. Scattered everywhere, it is the fulcrum upon which one presses in order to get away from the fear and domination of pain itself : in order to escape from the world, from the Vale of Tears. A man mortifies his breathing by making a virtue of pain, by its grace. Outside this use, pain is but a debasing hebetudo mentis.

He who reveals his pain, shows thereby that he is unable to use it as a treasure or as a descending weight which, by balancing the other ascending weight of not breathing, grants equipoise in mid-air, freedom. Secretum meum pro me, as St. John of the Cross and St. Teresa would say.

The secret leaks out, unaware of itself, whenever one is prompted by robust metaphors, as when Balzac wrote in his Eugénie Grandet: "In the moral or in the physical life there is a breathing in and a breathing out : the soul needs to breathe in the feelings of another soul, assimilating them so as to return them to it enriched. Without this beautiful human phenomenon, he (the man) extinguishes life in his heart, he lacks air, he suffers and wastes away" ; but the "other soul" can be being itself, when the breathing of the soul and the breathing of the body will form one single whole.

NOTES

[1] With a hymn one addresses one of the intermediate spiritual beings whereas with a psalm one penetrates through all the spheres : this was the common doctrine.

[2] One of the famous Tantric prescriptions mentioned by Avalon in The Serpent Power (Ganesh, Madras) begins by introducing the One into the Muladhara, Svatishtana and Manipura, `seats of greed, lust and angor' (below the navel), in order then to move on immediately to the Ajna, between the eyebrows and thence downwards towards the heart. The same points were detected by Gichtel among Western mystics.

[3] In illustrations of Greek manuscripts monks would sometimes be shown with their heads between their knees. This pose is prescribed by physicians in certain diseases of the heart.

[4] Certain positions that may help to get the "feeling" of the two nostrils are described in A System of Caucasian Yoga, by C. Walewski, published by the Falcon Wings Press, Indian Hills, Colorado, 1955. The method is said to be of Zoroastrian origin.

[5] In Taoism it is said that life penetrates into the body through the breath which inside the stomach blends itself with the Essence enclosed in the "Field of Cinnabar" below the navel, and thus from them the spirit is begotten. Death is separation of breath and essence. The initiate causes his breath to go down as far as the Field, from there he pushes it through the spine as far as the brain whence he makes it go down again into the chest and once this is done he lets it go through into the parts that are sick. These operations are impossible unless one nourishes the spirit with the consent of the body's gods, attracted by pure life and by good deeds but adverse to the smell of blood and garlic. The body's demons hostile to the work are called "worms" or "corpses" (Maspero, Les procédés de nourrir le principe vital dans la religion taoiste ancienne, in Journal Asiatique, April-September 1937). On the uses of breath or ch'i much can be learned from Matgioi's La voie rationnelle (Paris, 1907).